GH₵1 Fuel Levy Hike: A Step Backward for Fair and Transparent Economic Policy

Africa Policy Lens is deeply concerned about the Ghanaian Parliament's rushed approval of a new GH₵1-per-litre tax on fuel under a "certificate of urgency." Late on June 3, 2025, Parliament amended the Energy Sector Levies Act to increase the Energy Sector Shortfall and Debt Repayment Levy on petrol and diesel by GH₵1 – raising it to GH₵1.95 per litre for petrol and GH₵1.93 for diesel. Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) was exempted. This statement provides historical context on Ghana's fuel levies, examines inconsistencies with the 2025 national budget, explains how fuel prices are determined, and analyzes the likely impact on vulnerable citizens and recent disinflation gains. We conclude with an urgent call for fiscal responsibility, transparency, and protection of the economically vulnerable.

Background: Ghana's Fuel Levies and ESLA History

For decades, successive governments in Ghana have turned to fuel taxes and levies as an "easy to collect" revenue source. Demand for petrol and diesel is relatively inelastic, making such taxes a quick way to mobilize funds for public coffers. By the mid-2010s, a patchwork of fuel levies existed – including a Tema Oil Refinery (TOR) Debt Recovery Levy, a Road Fund levy for road maintenance, and other charges – many introduced to tackle specific crises.

In December 2015, facing mounting debts in the energy and road sectors, the government passed the Energy Sector Levies Act (ESLA), 2015 (Act 899) under a certificate of urgency. This law consolidated multiple existing fuel taxes and levies into a harmonized framework. The ESLA's purpose was to streamline energy-related taxes and channel the proceeds toward clearing legacy debts of state-owned utilities, stabilizing power supply, and financing road infrastructure. Government officials at the time justified the levies as necessary to rescue Ghana's struggling power companies and end "dumsor" (persistent power outages) by servicing debt in the energy and road sectors.

Notably, the 2015 ESLA law was pushed through Parliament in just days, with almost no public consultation, despite the significant burden it placed on citizens. Civil society organizations like the Africa Centre for Energy Policy (ACEP) warned early on that imposing hefty taxes without transparency or stakeholder input could erode public trust. Over-reliance on petroleum levies also carries macroeconomic risks; ACEP cautioned that piling taxes on fuel can stoke inflation, slow growth, and aggravate social hardships.

A decade on, Ghanaians are still paying numerous levies at the pump. The ESLA framework remains in effect, and its revenue-generating power has grown. According to the Ministry of Finance, total collections from ESLA levies from January 2016 through December 2024 amounted to GH₵27.2 billion. By May 2025, that figure exceeded GH₵29 billion. These are staggering sums – evidence that Ghana's motorists and businesses have contributed immensely, expecting relief from power crises in return. Yet the energy sector's financial woes persist. The new GH₵1 fuel levy ostensibly targets a $3.1 billion energy sector debt as of March 2025, on top of funding a projected $2.23 billion shortfall for 2025's power supply costs. Ghanaians are justified to ask: what impact have previous levies had, and why are more taxes still needed?

Unannounced Tax Hike vs. 2025 Budget Promises

This sudden fuel tax hike was not disclosed in the 2025 national budget, raising concerns about transparency and good faith. In fact, just three months ago, the Finance Minister explicitly assured Parliament that existing energy levies would be reviewed but not increased. In his March 2025 budget speech, Dr. Cassiel Ato Forson stated: "Without increasing the levy, we will review the Energy Sector Levies Act to consolidate the Energy Debt Recovery Levy, Energy Sector Recovery Levy (Delta Fund), and Sanitation & Pollution Levy into one...". This pledge suggested rationalizing levies for efficiency – not hiking them.

Now, that promise has been broken. Pushing through a GH₵1-per-litre increase under a certificate of urgency – with minimal debate or public input – contradicts the principles of accountable fiscal policymaking. The Minority in Parliament rightly decried the move as an unfair surprise and staged a walkout in protest. They argued that such a major tax change deserved proper scrutiny and that ramming it through without a quorum undermined democratic process.

Government claims that "exceptional circumstances" necessitated urgent passage do little to assuage the transparency concerns. The truth is, this levy was not signaled to citizens ahead of time, denying businesses and households the chance to plan. It also raises questions of fairness: if the 2025 budget (approved only months ago) did not warn of new taxes, on what basis is the government now burdening Ghanaians with extra fuel costs? The abruptness suggests a reactive revenue grab rather than a well-considered policy.

Officials appear to be taking advantage of a temporary lull in fuel prices. A combination of falling global oil prices and a rebounding Ghanaian cedi in recent months drove pump prices down to their lowest levels in over a year. As of end-May, petrol was selling around GH₵12.50 per litre (from highs near GH₵16 earlier in 2025). The Ministry of Finance argues this created "fiscal space" to introduce the new levy without an immediate price shock to consumers. Indeed, transport unions had even cut fares by 15% in response to the fuel price drop.

However, Africa Policy Lens finds this approach short-sighted. Windfalls from currency gains or oil dips are not a blank check for new taxes. If anything, such moments of relief should be used to strengthen economic resilience – not quietly impose fresh burdens. By the Finance Ministry's own admission, the levy's impact will be muted only so long as the cedi stays strong and world oil prices remain low. Any reversal in those trends will quickly translate into higher prices at the pump. Policy made by stealth, even if conveniently timed, erodes public confidence. Ghanaians deserve consistency between what is promised in the budget and what is delivered.

How Ghana's Fuel Prices Are Determined

To appreciate the weight of this new levy, it is important to understand Ghana's fuel price build-up mechanism. Since deregulation in 2015, retail pump prices are set bi-weekly by Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs) within guidelines overseen by the National Petroleum Authority. Several key variables drive the final price per litre:

• International benchmark prices: Ghana currently imports almost all refined petroleum products, due to the idleness of the Tema Oil Refinery. This means world market prices (e.g. the benchmark Platts prices for gasoline and diesel) directly influence our ex-refinery cost. All expenses for shipping, insurance, and handling imported fuel are added to the refinery price before fuel is sold to OMCs. If global oil prices rise, Ghana's fuel costs inevitably rise.

• Exchange rate (Forex): Fuel imports are purchased in U.S. dollars, so the cedi–dollar exchange rate is a critical factor. When the cedi depreciates, importers need more cedis to buy the same quantity of fuel, pushing up local prices. Conversely, cedi appreciation (as seen in May 2025) helps bring prices down. For example, if an OMC pays $1 per litre on the world market, a rate of GH¢12.00 per $1 would translate to GH¢12.00 per litre before taxes. A stronger cedi means fewer cedis per dollar and thus cheaper fuel domestically – all else being equal.

• Taxes and Levies: The government imposes a host of taxes, levies and statutory fees on each litre of fuel, which significantly determine pump prices. At present, there are roughly a dozen different taxes/levies on petroleum products – a combination of legacy charges and newer ones. These include the Energy Debt Recovery Levy (now being hiked), Road Fund levy, Energy Fund levy, Price Stabilisation and Recovery Levy (PSRL), Sanitation and Pollution Levy, Energy Sector Recovery Levy, Special Petroleum Tax, and others. Prior to this GH₵1 increase, taxes and levies already amounted to about 40% of the fuel price structure. For instance, in late 2021, when petrol was about GH¢6.90 per litre, roughly GH¢2.70 of that (40%) was due to taxes/levies. Today, with petrol around GH¢12–13, the total taxes per litre are even higher in absolute terms – well over GH¢3.00. These charges are a major component of what consumers pay, and the new levy further tilts the balance toward taxes in the price build-up.

• Distribution Margins: Beyond government charges, various margins for supply chain players are built into the price. Importers (Bulk Distribution Companies) add a margin to cover their costs and profit. OMCs then add their marketing margin. There are also fixed dealer/retailer margins for filling station operators, and allowances for transportation (known as Primary Distribution Margin). While individually smaller than the taxes, these margins ensure the fuel supply chain remains commercially viable. In total, however, studies show that taxes plus margins can constitute roughly 50% of the ex-pump price in Ghana, with the rest being the actual fuel cost (determined by world price and forex).

It is worth noting that one levy – the Price Stabilisation and Recovery Levy (PSRL) – was designed to stabilize fuel prices by accumulating funds when prices are low and subsidizing when prices rise. In practice, however, the PSRL has been frequently suspended or diverted for other uses. For example, it was suspended for a period in late 2021 to cushion consumers. This underscores a broader issue: even when Ghanaians pay levies ostensibly to solve a problem (be it price volatility or energy debt), those funds are not always transparently applied to that problem.

In summary, Ghana's fuel prices are a product of global market forces, the strength of our currency, and a substantial stack of domestic taxes and margins. The newly passed GH₵1 levy directly increases the tax component of prices. While the government argues that current low world oil prices and a strong cedi will "absorb" this hike in the short term, any adverse turn in those conditions could swiftly feed through to higher costs at the pump.

Impact on Consumers: Regressivity and Risk to Disinflation Gains

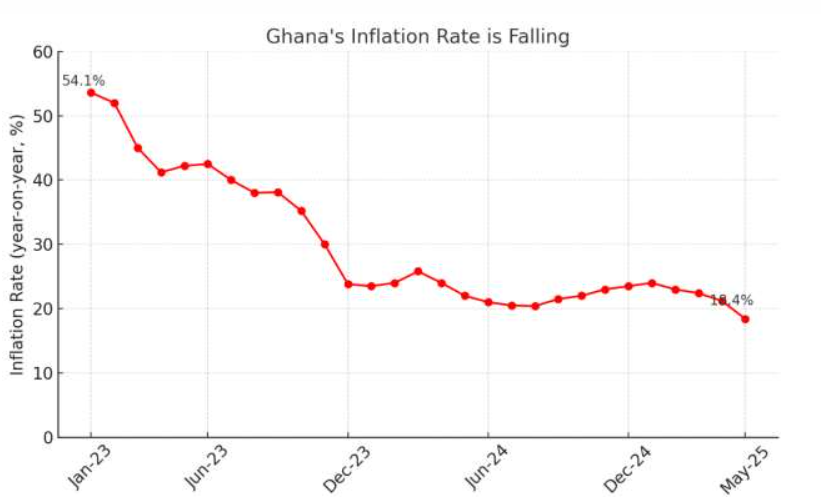

Figure: Ghana's year-on-year inflation peaked at 54.1% in Dec 2022 amid a currency crisis, but eased to about 21% by April 2025 as the cedi stabilised and fuel prices fell. This hard-won disinflation provided relief to consumers. A sudden new fuel levy, however, threatens to undo these gains if global oil prices rebound or the cedi weakens, driving pump prices back up.

The GH₵1 fuel levy is a flat charge per litre, making it a regressive tax measure. Whether one is a wealthy executive or a poor farmer, each will pay an extra cedi for every litre of fuel consumed. But in relative terms, the burden on the poor is far greater. Lower-income households spend a larger share of their income on transportation, cooking fuel, and goods whose prices heavily depend on fuel costs. When fuel prices rise, the cost of public transport (tro-tros, buses, taxis) typically goes up, and the prices of essentials – from food to market goods – increase due to higher haulage and distribution costs. This new levy will gradually filter into the economy, putting disproportionate strain on the poorest Ghanaians who can least afford it.

It is especially troubling that this policy arrives just as Ghana was making solid progress in taming inflation. Over the past year and a half, inflation has been on a downward trajectory, dropping from historic highs above 50% to about 18%–21% recently. Analysts attribute this disinflation in part to more stable fuel prices and a recovering cedi, alongside tight monetary policy. For example, petrol and diesel price declines earlier this year contributed to consecutive months of slowing inflation. The inflation rate fell to 21.2% in April 2025, the fourth month of decline in a row. The Bank of Ghana now pegs current inflation at 18.4% – the lowest in over two years – and forecasted further easing if no major shocks occur.

However, a fuel tax shock is exactly the kind of event that could reverse this positive trend. If global oil prices creep up or the cedi slips even modestly, the new GH₵1 levy will amplify the impact on pump prices, potentially pushing inflation back up. Even government sources concede that the levy's pain is "hidden" only so long as other factors are favorable. "If either trend reverses – if oil prices rise or the cedi depreciates – the tax could undo recent gains in consumer relief," one analysis warns. In other words, Ghana's recent hard-won inflation relief is at risk.

Moreover, the timing could not be worse for ordinary citizens. Just last week, drivers and commuters were celebrating fuel price reductions, however modest. Public transport fares were cut by 15%, offering a bit of breathing room in household budgets. All that relief may soon evaporate. As Mr. Duncan Amoah, Executive Secretary of the Chamber of Petroleum Consumers (COPEC), noted, "This week we were happy about the 50 pesewa fuel price reduction... but if now we must pay an extra 1.00 cedi, the relief will be lost from our pockets". He estimates that petrol selling at GH¢12.52 will effectively jump to GH¢13.52 per litre once the levy fully reflects at the pumps. Any further currency depreciation could send prices "back to the high levels we protested against", with "dire consequences for all of us," Mr. Amoah warned. In sum, this levy acts like a hidden fare hike on every taxi or tro-tro ride and a stealth price increase on goods and services across the board.

Finally, we must emphasize the cumulative burden on the vulnerable. In the past two years, Ghanaians have endured economic hardships — job losses, pay cuts, and a cost of living crisis — during Ghana's worst economic downturn in a generation. Inflation above 50% ravaged real incomes in 2022. While the situation has slightly improved, things are still tough: over 20% inflation means prices are still rising, just more slowly. Introducing a new consumption tax on fuel at this juncture effectively kicks people when they are down. It will reflect in market food prices and transport fares that directly hit the poor. We fear this could push many more Ghanaians below the poverty line or aggravate urban unemployment as businesses face higher operating costs.

The Way Forward: Fix Structural Problems, Don't Tax a "Leaking Bucket"

Africa Policy Lens acknowledges that Ghana's energy sector faces a real fiscal crisis. The intention behind the levy – to raise an estimated GH₵5.7 billion annually for shoring up power sector finances – addresses a legitimate problem. We agree that ensuring stable electricity supply ("ending dumsor") and paying down energy sector debt are critical goals. However, we strongly disagree that yet another tax on consumers is the optimal or sustainable solution.

The core issues behind Ghana's energy sector shortfall are structural inefficiencies and governance failures – essentially, a "leaking bucket" into which taxpayers' money has been poured for years. Even the Ministry of Finance has admitted that fundamental problems like poor revenue collection, high system losses, weak enforcement of payment mechanisms, and expensive power contracts are to blame for the sector's perpetual losses. Adding a tax addresses none of these. As COPEC's Duncan Amoah aptly put it, "You cannot continue to pour water into a leaking bucket, so we need to resolve the issues crippling the power sector." Every cedi raised via this levy will go into the same broken system – and could vanish without lasting impact unless those systemic leaks are fixed.

Indeed, Ghanaians have heard many promises that painful levies would yield improvements. In 2016, the ESLA was sold as the cure to energy debt. In 2021, new levies (like the Sanitation levy and "Energy Sector Recovery" levy) were added, again to supposedly solve problems. Yet today, in 2025, the energy sector's debt sits at $3.1 billion and power outages still loom whenever the financial pinch worsens. Over GH₵29 billion collected via ESLA since 2016 has not meaningfully dented the energy sector's challenges. This record justifies public skepticism. We ask the government: If nearly GH₵30 billion in levies hasn't solved the problem, will an extra GH₵5.7 billion a year do the trick without deeper reforms? Simply taxing Ghanaians more "without addressing the fundamental inefficiencies ... will ultimately sabotage ongoing economic stabilisation efforts," as Mr. Amoah warns.

Africa Policy Lens therefore urges a two-pronged approach going forward:

1. Tackle the Structural Flaws

The government must prioritize stopping the bleeding in the power sector over using new taxes as a bandage. This means aggressively reducing technical and commercial losses in electricity distribution (which currently waste 20–25% of power output). It means enforcing bill collection – even from government entities – and reforming the opaque cash waterfall mechanism so that revenues are properly allocated to generation and fuel costs. Renegotiating exorbitant take-or-pay contracts with independent power producers and accelerating gas supply projects would also reduce the reliance on expensive liquid fuels for power generation. These are complex tasks, but without them, any levy is just "more water in a leaking bucket."

We note proposals to involve the private sector in electricity distribution (e.g. reviving aspects of the ECG concession) and encourage transparent dialogue on such reforms. The long-term solution to Ghana's energy woes is improved efficiency and accountability, not perpetual taxation.

2. Ensure Transparency & Accountability for Levy Proceeds

If the GH₵1 levy is to remain in place, the government must demonstrate unprecedented transparency in its usage. Ghanaians have a right to know how much revenue this levy generates and exactly how those funds are applied. We call on the Ministry of Finance and ESLA Plc to publish quarterly reports detailing the levy collections and disbursements – for instance, how much went to service specific debts, purchase fuel, or invest in infrastructure. As the adage goes, "show your work." Without clear reporting, public skepticism will justifiably mount. Furthermore, there should be a sunset clause or clear conditions for this levy's review and removal. Is this a temporary five-year measure until debts reach a certain level? Or will it be scrapped once tariffs are adjusted? Government must communicate a strategy, lest this "urgent" tax quietly become permanent like so many before it. Transparency is essential: if Ghanaians can see tangible results – say, a declining energy debt stock and fewer blackouts – they may be more understanding of the sacrifice. But absent that, the levy will breed resentment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Africa Policy Lens opposes the manner in which the GH₵1 fuel levy was introduced – without prior notice, under a rushed process, and in a way that burdens ordinary citizens who are just regaining their economic footing. We urge the Government of Ghana to reflect on the historical lesson here: sustainable solutions come from reform, not just revenue. We stand with the many civil society voices insisting that Ghana pursue fiscal responsibility and social justice hand in hand. Any sacrifice asked of the public should be matched with genuine governance improvements and protections for the poor.

As an advocacy organization, we will be monitoring the implementation of this levy. We will hold the government to its word that the funds will "secure a stable power future" and not be mismanaged. We also call on development partners and oversight bodies to support Ghana in auditing and improving the energy sector. The Ghanaian people have contributed "one cedi, just one cedi" per litre toward ending dumsor – now it is time for the leadership to deliver on their end of the bargain with transparency, accountability, and real results.

-- End of Press Statement --