Short-Term Fix, Long-Term Risk: Ghana's 2025 Debt Path Demands Urgent Rethink

Ghana’s Borrowing Between January and May 2025 – Africa Policy Lens (APL)

Accra, 26 May 2025: Africa Policy Lens (APL) has conducted an analysis of the Government of Ghana’s borrowing activities from January through May 2025. The review finds that Ghana’s public debt has continued to rise in early 2025, with total debt now about GH¢769.4 billion (≈US$49.5 billion) as of end-March 2025. This marks an increase of roughly GH¢42.7 billion in the first quarter alone. While the surge in borrowing reflects the government’s efforts to finance essential expenditures amid economic recovery, APL urges a cautious approach going forward. We acknowledge the legitimate fiscal needs driving these loans, yet we remain concerned about emerging debt trends – including heavy reliance on short-term domestic instruments, rising interest costs, and rollover risks – that could undermine Ghana’s debt sustainability if not carefully managed.

Debt Accumulation in Early 2025 – Overview

Ghana’s total public debt stock climbed to GH¢769.4 billion by end-March 2025 (about 55% of GDP), up from GH¢726.7 billion at the end of 2024. This GH¢42.7 billion increase in Q1 2025 comprises both domestic and external borrowing. In cedi terms, external debt edged up to approximately GH¢442.5 billion (US$28.5 billion) in March, while domestic debt reached GH¢326.9 billion. Notably, most of the jump occurred in January–February (total debt was GH¢752.1bn in January and GH¢768.1bn in February), with a smaller uptick in March. The Bank of Ghana attributes part of the Q1 debt growth to cedi depreciation early in the year, which increased the local currency value of external obligations. However, by April–May the cedi staged a strong rally, appreciating about 24% against the US dollar. This currency strength is mitigating the cedi-value of external debt and helped keep the total debt stock fairly stable going into Q2 2025 (in dollar terms, Ghana’s debt actually rose only marginally from $49.4bn in Dec 2024 to $49.5bn by March 2025). APL views the cedi’s rebound and resulting relief in debt metrics as positive developments, but only temporary – fundamental debt burdens remain high and will require sustained fiscal discipline to contain.

Domestic Borrowing Trends – Heavy Reliance on T-Bills

Domestic borrowing has largely driven Ghana’s new debt accumulation in early 2025. With Ghana still shut out of international capital markets post-default, the government has leaned heavily on the domestic market to finance its deficit. In practice, this has meant an over-reliance on short-term Treasury bills and a few privately placed bonds, as the normal medium- to long-term bond auctions have not fully resumed since the 2023 domestic debt exchange. According to the Ministry of Finance’s data, short-term securities (Treasury bills of 1 year or less) constituted the bulk of new issuance in 2023 and continued to dominate in 2024. The Finance Minister’s 2025 Budget signaled plans to cautiously re-open longer-term bond issuance during 2025, but so far in the first months of 2025, T-bills remain the primary borrowing tool.

Importantly, Treasury bill interest rates have been trending downward over the past year, which provides some relief. After peaking around 28–30% in late 2024, T-bill yields have declined sharply – by March 2025 the 91-day yield was in the low 20% range, and by April it had fallen to around 15.5%. This drop reflects easing inflation and efforts by authorities to reduce government borrowing costs. Lower yields mean the government currently pays less interest on new T-bills issuance, and recent auctions have even been oversubscribed at these lower rates, indicating improved investor confidence. APL welcomes this moderation in domestic interest rates, but notes that it has been achieved partly through administrative measures (such as the Bank of Ghana rejecting excessively high bids). The government must be careful – artificially suppressing yields or relying on central bank intervention is not a sustainable long-term strategy and could backfire if market appetite shifts.

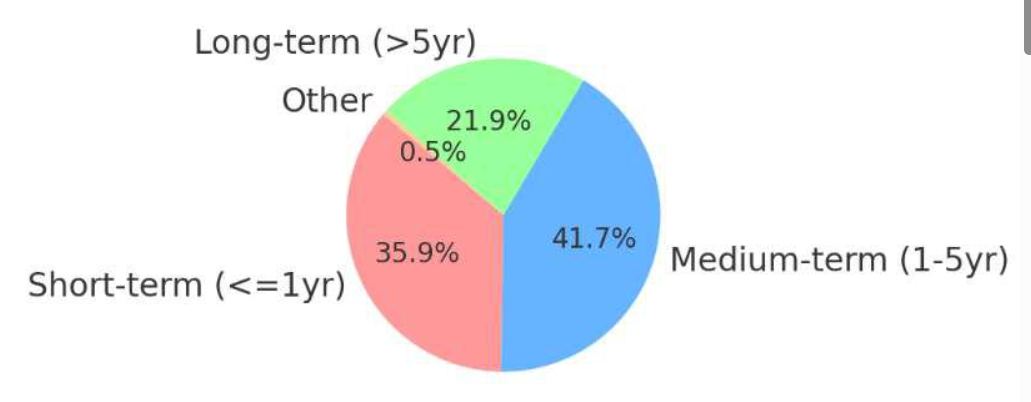

Figure 1: Composition of Ghana’s Domestic Debt by Maturity (End-2024).

Source: Data from Ghana’s Ministry of Finance (2025)

The government’s reliance on T-bills has skewed the debt structure toward short tenors – shortterm instruments comprised about 36% of domestic debt as of Dec 2024, up from 26% a year earlier. Medium-term (1–5 year) debt accounts for ~42%, while long-term (>5 year) is just ~22%

This heavy short-term borrowing bias means Ghana’s debt profile has a significant rollover risk. Much of the domestic debt must be refinanced frequently – in 2024, total domestic maturities (redemptions) reached GH¢217.5 billion (a 62% jump from 2023), implying the government had to constantly roll over obligations coming due. For 2025, a substantial volume of T-bills outstanding will likewise mature every few weeks, perpetuating a “borrow today to repay yesterday” cycle. APL is concerned that such short maturities expose the government to liquidity shocks – any turbulence in the T-bill market or a dip in investor demand could make rolling over debt at affordable rates very challenging. We saw a hint of this risk in March 2025 when the domestic debt stock actually dipped slightly (from GH¢328.0bn in Feb to GH¢326.9bn in Mar) as the government scaled back T-bill issuance amid shifting appetite. While exercising issuance restraint can be prudent, Ghana must still refinance existing debts – meaning any funding shortfall in a given auction could create cash crunches or force reliance on the central bank.

Another notable trend is the changing investor base for domestic debt. As of end-2024, local private investors (individuals, firms, and other institutions) have become the dominant holders of Ghana’s domestic debt, overtaking banks. Ministry of Finance data show that the non-bank sector held 51.5% of domestic debt in 2024, up from 43.6% the year prior, while the banking sector’s share fell to 43.8%. This suggests the government is increasingly tapping households and non-bank institutions to buy instruments like T-bills – likely a response to banks reaching exposure limits and foreign investors exiting the market. Broadening the investor base can be positive, but it also indicates the state is leaning on every available pocket of local liquidity. APL cautions that many of these private investors are sensitive to interest rates and confidence in government policy; maintaining their trust is essential. Opaque “private placement” bond issuances (where government negotiates debt directly with specific investors, often at high yields) are particularly worrying in this regard – such deals lack transparency and can carry steep costs. Analysts have warned that Ghana’s reliance on short-term bills and off-market placements is not sustainable and could undermine debt sustainability if it persists. We echo these concerns and urge a return to normal, transparent auctioning of medium- and long-term bonds as soon as market conditions allow.

External Borrowing and Debt Stock Evolution

On the external front, Ghana’s external debt stock has seen only a modest increase in 2025 so far. In dollar terms, external debt rose slightly from about $49.4 billion at end-2024 to $49.5 billion by March 2025. The IMF, World Bank, and other official creditors remain the main sources of new external financing, as Ghana cannot currently access international bond markets due to its ongoing debt restructuring. Indeed, Ghana effectively defaulted on most of its foreign debt in 2022, and discussions with Eurobond holders and bilateral lenders are continuing into 2025. This means no new Eurobond issuance has been possible – a sharp contrast to the pre-2022 period when Eurobond borrowing was a key source of budget financing. Consequently, external debt accumulation in early 2025 reflects mainly disbursements under the $3 billion IMF program (ECF) and other project and budget support loans from multilateral and bilateral partners. For example, Ghana received around $600 million tranches from the IMF in 2023 and may receive similar inflows in 2025 upon successful program reviews. These official loans typically come on concessional terms and are critical for plugging financing gaps while commercial sources are closed off.

Crucially, the cedi’s exchange rate movements have had a big impact on the reported size of external debt in local currency terms. During January–February 2025, the cedi experienced some depreciation, which drove the external debt (measured in GH¢) higher – reaching GH¢440+ billion by February. By contrast, the strong cedi rally by May 2025 has reduced the GH¢ value of external debt. At a current rate of roughly GH¢11.8 per US$1, Ghana’s $28.5bn external debt translates to about GH¢337 billion, significantly lower than the GH¢442 billion level seen in Q1 when the cedi was weaker. In other words, exchange rate gains have provided temporary debt stock relief. APL applauds the Bank of Ghana’s efforts to stabilize the currency – a combination of tightened monetary policy, forex interventions, and improved trade balance has made the cedi one of the world’s best-performing currencies in 2025. However, we underscore that currency appreciation alone does not solve the debt problem. It can buy time by easing external debt servicing costs (e.g. interest and principal in cedi terms fall), but the debt in dollar terms remains and must eventually be repaid. Ghana’s external debt, now about 29% of GDP, is still unsustainably high given limited fiscal buffers. The government should use this period of cedi strength and relative external debt stability to accelerate negotiations on debt restructuring - securing meaningful relief from external creditors would improve long-term debt indicators far more substantially than short-term currency movements.

Ghana’s substantial domestic debt pile (2018–2022). Domestic debt (light blue) grew dramatically in recent years, making up an increasingly large share of the total public debt by 2022. Heavy domestic borrowing pushed Ghana’s debt-to-GDP ratio to ~93% by end-2022, precipitating the 2023 debt restructuring. Though the ratio has since declined (≈55% of GDP in Mar 2025) due to economic growth and the restructuring, overall debt remains elevated.

The above chart highlights the explosive growth in Ghana’s debt prior to the ongoing adjustment – total public debt surged from the equivalent of 63% of GDP in 2019 to 92.7% of GDP by 2022. Much of this increase was driven by domestic borrowing (the light blue portion), which became unsustainable and forced Ghana to undertake an unprecedented Domestic Debt Exchange (DDE) in 2023. That painful episode – which saw local bondholders absorb losses through lower interest rates and extended maturities – has helped to temporarily stabilize debt levels. Indeed, Ghana’s debt-to-GDP ratio has improved in 2024–25 partly because the economy expanded (inflation and rebasing boosted the GDP denominator) and because debt growth slowed during the restructuring period. APL notes, however, that debt stabilization is not the same as debt reduction. Ghana’s public debt stock is still rising in absolute terms (now nearing GH¢770 billion) and the underlying fiscal deficit remains sizeable, requiring continued borrowing. The 2025 Budget projects an overall fiscal deficit of 7.7% of GDP (or 3.1% on a commitment basis) to be financed by GH¢36.8bn in domestic borrowing and GH¢21.4bn external loans. If implemented, this would further add to the debt pile. It is therefore imperative that Ghana anchors its debt on a sustainable path through prudent management, even as it meets short-term financing needs.

Rising Interest Costs and Debt Service Burden

One of the most alarming trends associated with Ghana’s recent borrowing is the soaring interest cost on public debt. Years of high interest rates and increased debt stock have translated into a heavy debt service burden for the government. In 2024, interest payments consumed roughly 16.8% of total government expenditure and about half of tax revenues. For 2025, interest costs are projected to climb even higher – the budget allocates GH¢64.2 billion to interest payments, which is nearly 24% of total spending and about 29% of expected revenues. This means almost one out of every four cedis spent by government next year would go to creditors as interest, a stark indicator of how debt is eating into Ghana’s fiscal space. By comparison, the government plans to spend only GH¢32.9bn on capital investments in 2025. In essence, interest costs are now double the development budget, crowding out critical investments in infrastructure, education, health, and other public services.

APL finds this trajectory of rising debt service deeply concerning. High interest obligations constrain the government’s flexibility to respond to economic needs and shocks. They also create a self-reinforcing cycle – as more revenue is used to service debt, fewer resources are available for growth-enhancing projects, which in turn can dampen economic growth and revenue generation, making it harder to pay down debt. Furthermore, Ghana’s interest payments are skewed towards the domestic side, where rates have been higher. Following the debt restructuring, domestic interest payments actually increased in 2024 (as new bonds carry stepped-up coupons over time and a large stock of T-bills remained at high yield until recently). For instance, total domestic interest paid in 2024 was around GH¢46.8bn, up from the prior year – reflecting the cost of servicing a growing stock of short-term debt. External interest, while at lower rates, is also substantial and foreign exchange-intensive. Without question, Ghana’s current debt service profile is unsustainable. The IMF and World Bank have emphasized the need for comprehensive debt restructuring precisely to reduce this burden. Ghana has started on that path (domestic debt restructured, external in progress), but until relief is fully secured and fiscal consolidation firmly takes hold, interest costs will remain a perilous strain on the budget.

A Balanced View – Legitimate Needs vs. Sustainability Concerns

APL recognizes that Ghana’s government faces a difficult balancing act. On one hand, borrowing in early 2025 has been driven by legitimate fiscal needs: to fund public sector salaries, essential services, and economic recovery initiatives at a time when domestic revenue mobilization is still ramping up. The first quarter of 2025 saw relatively restrained fiscal deficits – the government recorded a 1.0% of GDP fiscal deficit and even a small primary surplus of 0.3% of GDP by March, indicating an effort to contain expenditures. This fiscal prudence, alongside tight monetary policy, has contributed to the cedi’s stabilization and a gradual return of investor confidence. We commend the authorities for these achievements and for avoiding unchecked spending so far. Indeed, Ghana’s ability to maintain primary budget discipline in a pre-election year (2024/25) is notable – it suggests a commitment to reform that deserves acknowledgement.

On the other hand, APL must underscore the risks of the current debt trajectory. The recent improvements (stronger currency, slight drop in debt-to-GDP ratio, lower T-bill rates) are built on a fragile foundation. They rely on temporary factors – e.g. large central bank forex interventions to prop up the cedi, and one-off debt reprofiling from the DDE – which cannot be counted on indefinitely. The underlying reality is that Ghana’s debt stock is high and growing; the government is still running deficits that require substantial borrowing every month, mostly from domestic sources. If Ghana were to stray from its fiscal reform path or if any shock were to dry up domestic financing, the situation could deteriorate quickly. Moreover, 2024 is an election year in Ghana, and historically election periods have led to fiscal slippages as outgoing administrations ramp up spending. Any significant unplanned spending or populist fiscal measures in late 2024 would worsen the debt outlook and erode the hard-won gains of stabilization. We urge all stakeholders – the government, opposition, and civil society – to maintain a focus on fiscal sustainability throughout the election cycle. Short-term political considerations must not derail the progress on consolidation, as the economic consequences of backsliding would be severe (e.g. another currency depreciation, loss of investor trust, and possibly a return to financing by money-printing).

Recommendations – Managing Ghana’s Debt Path Prudently

In light of the above findings, Africa Policy Lens offers the following cautions and recommendations to the Government of Ghana regarding prudent debt management:

- Gradually Restore Long-Term Domestic Funding: We urge the government to follow through on plans to re-open the domestic bond market in a cautious manner. Returning to medium- and long-term bond issuance (even if at slightly higher coupons initially) will help lengthen the maturity profile and reduce rollover pressures. It is encouraging that authorities aim to issue “large-sized benchmark bonds” to enhance liquidity – doing so will also signal to investors a commitment to normalizing the market. Any new bonds should be issued transparently via auction, with credible benchmark yields, to rebuild confidence. Over time, a successful resumption of domestic bonds can reduce the over-reliance on 91-day and 182-day T-bills. While T-bills will remain part of the financing mix, they should not carry the entire burden indefinitely. A healthy debt structure requires diversification of tenors

- Avoid Excessive Short-Term Rollovers: Until longer tenors are reintroduced, the government must manage its T-bill program very carefully. APL cautions against accumulating ever larger volumes of short-term debt that could become un-refinanceable in a stress scenario. We recommend setting prudent limits on net new T-bill issuance each quarter, aligned with what the market can absorb without rate spikes. If there are weeks of low demand, it is preferable to adjust spending or seek alternate financing (e.g. temporary IMF bridge financing) rather than force a high-cost rollover. The risks of a failed rollover – which could trigger payment defaults or disruptive monetary financing – are too grave. Building a small liquidity buffer when possible (e.g. using any revenue windfalls or IMF disbursements to hold some cash) would help insulate against auction shortfalls. Essentially, Ghana should not bet its finances on week-to-week T-bill sales – a more strategic approach to debt and cash management is needed in this interim period.

- Enhance Transparency and Accountability: We call on the Ministry of Finance to improve public disclosure around debt issuance and debt stocks. This includes timely publication of monthly debt bulletins and details of any private placements or nonstandard borrowing. The lack of transparency around bilateral private loans can breed

mistrust and mask the true debt picture. APL applauds the Ministry’s recent Debt Statistics Bulletins and urges that these continue on a quarterly (if not monthly) basis, with clear breakdowns of domestic and external components, maturities, and holder composition. Transparency will bolster confidence among investors (domestic and foreign alike) that Ghana’s debt management is above-board and under control.

- Rein in Interest Costs through Reforms: To address the crushing interest burden, the government must tackle the problem from both ends – reduce the cost of debt, and reduce the quantity of debt. On cost, as discussed, moving to longer maturities at reasonable rates will help, and successfully concluding the external debt restructuring will also lower interest (Eurobond coupons, for instance, could be cut substantially in any deal). On the quantity side, fiscal consolidation is key. The only sure way to stop debt from snowballing is to eliminate the underlying deficit over time. We encourage continued efforts to boost domestic revenue (through tax reforms and improved collection) and tightly prioritize expenditures. Every cedi of extra revenue or saved expense that can be channeled to reducing borrowing will pay dividends in lower future interest payments. Ghana should also explore liability management operations – for example, using some IMF inflows or other funds to retire especially costly debt (like certain domestic bonds or overdrafts) if feasible. Creative, proactive debt management can shave off interest costs at the margin. Above all, Ghana must avoid policies that would increase interest costs – for instance, any return to central bank deficit financing would be counterproductive, as it would fuel inflation and force interest rates back up. Discipline and reform are the surest route to bringing interest expenses down over the medium term

- Safeguard Debt Sustainability Targets: Under the IMF-supported program, Ghana has quantitative targets and thresholds to keep debt on a sustainable path. APL strongly advises the government to adhere to these targets and even build additional buffers where possible. This includes sticking to the primary surplus objectives, limits on nonconcessional borrowing, and careful vetting of new loan commitments. Any large new borrowing initiatives (especially if off-budget or through state-owned enterprises) should be avoided unless absolutely necessary, as they could jeopardize the delicate debt dynamics. We note that the debt-to-GDP ratio has fallen to ~55% partly due to statistical base effects – this should not invite complacency. Ghana’s own debt management strategy should aim to gradually lower this ratio further in coming years (toward the IMF’s suggested threshold in the 55-60% range for moderate risk). That will require restraining debt growth below the pace of GDP growth. In practice, this means persistently running primary surpluses and securing meaningful debt relief externally. APL urges continued engagement with creditors for debt relief and recommends against piling on new debt that could undo the progress.

- Plan for Post-2025 and Contingencies: We encourage Ghanaian authorities to look beyond the immediate horizon and develop a comprehensive medium-term debt management plan. This plan should outline how Ghana will handle upcoming debt peaks (for example, the new bonds issued under the DDE will have rising coupons and bullet maturities later in the decade that need planning). It should also consider contingency scenarios – such as further global economic tightening or domestic growth shortfalls – and how the government would respond without derailing debt sustainability. By preparing now for potential challenges (e.g. setting aside funds in a sinking fund when possible, or arranging precautionary credit lines), Ghana can avoid ad-hoc scrambling down the road. We also advise maintaining close coordination with the Bank of Ghana to ensure that monetary and debt management policies are aligned (e.g. avoiding excessive short-term debt that conflicts with monetary stability). A forward-looking strategy will reassure observers that Ghana is genuinely committed to exiting its debt distress and will not slip back into crisis.

Conclusion

In summary, Africa Policy Lens finds that Ghana’s borrowing between January and May 2025, while addressing immediate fiscal needs, is raising red flags that cannot be ignored. Total public debt continues to mount, driven predominantly by domestic short-term loans. Interest payments are eating a sizeable portion of the budget, and rollover requirements are high, indicating considerable vulnerability in the government’s financing strategy. At the same time, we note positive signs – the cedi’s strength, declining T-bill yields, and ongoing fiscal restraint – which suggest that prudent policies can indeed improve the debt outlook. The government’s challenge now is to lock in and build on those gains without reverting to old patterns.

APL urges the Government of Ghana to exercise utmost caution and foresight in managing the country’s debt. There is little room for error: a misstep in debt management or fiscal discipline could quickly unravel the recent stability. Conversely, a steadfast commitment to reform, transparency, and prudent borrowing can gradually steer Ghana out of the danger zone. Ghanaians have sacrificed a lot in the past two years – through inflation, austerity, and the debt restructuring – to restore macroeconomic stability. It is incumbent upon the authorities to honor those sacrifices by ensuring that Ghana’s debt remains sustainable going forward. Every borrowing decision should be vetted against the question: Does this keep us on a sustainable path, or put our future at risk?

Africa Policy Lens stands ready to support and advise on this journey toward debt sustainability. We will continue to monitor Ghana’s public debt trajectory and advocate for policies that balance the country’s development financing needs with the imperative of maintaining economic stability. Ghana’s story in early 2025 is one of fragile recovery – wise debt management will determine whether this recovery strengthens into lasting prosperity or falters under renewed financial stress. We are hopeful that, with prudent actions as outlined above, Ghana will choose the path of long-term fiscal health and avoid the perils of excessive debt. APL’s message to the government is clear: borrow wisely, manage debt responsibly, and safeguard Ghana’s economic future.